Pádraig Timoney

Champ on the Bow

December 6, 2024 – February 2, 2025

EN

Champ on the bow

Where did I read that ANY PLACE BUT HERE was the motto of all sailors? Born in Northern Ireland, yet not really bound within any territory or home, Pádraig Timoney settled in the ports of Naples and New York City in the past two decades. I met him in Berlin where he is “currently based”. One of his neighbors is Scottish cult artist Douglas Gordon—a chuckaboo of his, acclaimed for a 24-hour long appropriation of Hitchcock’s Psycho—with whom he shares a passion for football. His other neighbors are the English language bookstore Hopscotch Reading Room, specializing in anti-colonial, non-western, diasporic and queer perspectives, with whom he shares his working space, and Cutt Press, a sham clandestine factory that remakes/remodels rare books and editions. The sailor is among the pirates (from the Greek πειρατής, ‘brigand, pirate’, itself derived from πειρα, ‘trial, attempt, experiment’). Pádraig Timoney keeps on questioning the possibilities and the limits, or rather approaching the shores, of the media and materials, of what is indeterminate.

There are many traditions intended to bring good luck to a new project. As an experienced and well-read sailor, Pádraig sees the gallery as a ship and as it is launched proposes to inaugurate it by breaking a sacrificial bottle of champagne over its bow. A literary bottle of champ made of a bit of Marcel Duchamp and Marcel Proust or of Duchamp revamping Proust, even. See how the work Membranes, Thins, Past (2022), overtly translating Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past into photographic terms by shortening and deriding the magnum opus, constructs an image from a recording of what is a subjective experience. This becomes an invitation to reconsider the ordinary by distorting and recomposing the mundane—a secretive meditation on the shifting, often elusive boundaries between reality and perception based on retinal stimulation, between abstraction and figuration.

Deploying a diverse and expansive repertoire from paintings to photographs and mirrors, the work channels the fluidity of time and the slipperiness of meaning. And if Beckett is not mentioned this time, he is definitely part of the referential crew. For his poetics—an aesthetics of fragments, not formlessness, but dissolution of form, an entropic mixture of words, Wrassem (2024) means ‘painter’ in Arabic, chemical treatments or sparkling rabbit skin glue—pervade the work. Perhaps Samuel Beckett is the parrot on the sailor’s shoulders that pleads: “Don't expect to make sense, don't expect to know the referential image”. According to Pádraig, the best text explanation of the monologue of Lucky from Waiting for Godot is undoubtedly no explanation.

The most remarkable features that keep coming and going in past reviews of Pádraig’s work, as the relentless Atlantic surf outlines cliffs in Ireland, are the “versatility” and the “heterogeneity” of a “mercurial” practice (sheer music to my ears), unfurling different styles and modes of painting, even (I read it twice) offering the illusion that one views a group exhibition rather than a solo one.

As another literary fellow islander of his would say: “I’m not one and simple but complex and many.” Maybe, with all due respect to Virginia Woolf, he’s just one and complex and there’s no cognitive dissonance in this. Nothing stands in the way, things come together. He under-promises and over-delivers, while artists who, say, think they need to defend a style, a name or a reputation often over-promise and under-deliver.

When Pàdraig invited me to write a text about this group of works, I thought at first that it would be an opportunity to disclose and in a certain sense, demystify his approach—to guide the viewer and allow an active participation in the unravelling of the meaning and the purpose of the works… But would it then be assumed that the works don’t speak for themselves? As a believer in the tension between verbal and visual signification, I trivially tend to assume that they don’t and my practice might be an effort, an attempt (πειρα), to make sight and meaning match. Though, when the invitation comes with a brief “be free” and emanates from an artist who makes mirror works, no one more than I could appreciate this call for total freedom and self-exploration to the core.

Thinking back about me looking at my reflection through the blue and gilded surfaces of his Blue Mirror 1 (2022) and AuAgNY Mirror (2023) at the Berlin studio, I can’t help but think that a critical text that is supposed to reflect an artist's work reflects more upon its own author than the work itself. Here, the writer and the viewer turn blue and gilded. This recalls the famous argument between intellectual guru Susan Sontag, of whom many complained that her cerebral way of elaborating on art was a bore, and legendary and elusive artist Paul Thek, who, running out of patience, finally told her: “Susan, stop, stop. I'm against interpretation. We don't look at art when we interpret it. That's not the way to look at art.” The end of the story is known to all. She dedicated her 1966 collection of critical essays to Thek, and with good reason: the book was entitled Against Interpretation.

So, let’s look at art and be free!

Text by Tristan Bera

DE

Wo habe ich gelesen, dass any place but here (dt. überall, nur nicht hier) das Motto aller Seeleute ist? Pádraig Timoney, in Nordirland geboren, aber nicht wirklich an ein Territorium oder eine Heimat gebunden, hat in den letzten zwei Jahrzehnten in den Häfen von Neapel und New York City festgemacht. Ich habe ihn in Berlin getroffen, wo er „zur Zeit lebt und arbeitet“. Einer seiner Nachbarn ist der schottische Kultkünstler Douglas Gordon – ein alter Kumpel, bekannt für seine 24-stündige Adaption von Hitchcocks Psycho – mit dem Timoney seine Leidenschaft für Fußball teilt. Seine beiden anderen Nachbar*innen sind die englischsprachige Buchhandlung Hopscotch Reading Room, die sich auf antikoloniale, nicht-westliche, diasporische und queere Perspektiven spezialisiert hat und mit der sich Timoney einen Arbeitsbereich teilt, und Cutt Press, eine vermeintlich geheime Fabrik, die seltene Bücher und Editionen neu auflegt/umgestaltet. Der Seemann ist unter den Piraten (von griechisch πειρατής, »Räuber«, »Pirat«, wiederum abgeleitet von πειρα, »Probe«, »Versuch«, »Experiment«). Pádraig Timoney hinterfragt immer wieder die Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Medien und Materialien – des medial Unbestimmten, dessen Ufern er sich annähert.

Es gibt viele Traditionen, die einem neu begonnenen Projekt Glück verheißen sollen. Als erfahrener und belesener Seefahrer betrachtet Timoney die Galerie als Schiff und schlägt vor, sie beim Stapellauf mit einer am Bug zerbrochenen Champagnerflasche zu taufen. Ein literarischer Schampus, wenn man so will, mit einem Schuss Marcel Duchamp und Marcel Proust, oder sogar mit einem von Duchamp aufgepeppten Proust. Man beachte, wie die Arbeit Membranes, Thins, Past (2022), die Prousts Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Zeit unverhohlen in fotografische Begriffe übersetzt, indem Timoney das Magnum Opus persifliert, aus der Aufzeichnung einer subjektiven Erfahrung ein Bild konstruiert. Es ist eine Einladung, das Gewöhnliche zu überdenken, indem das Alltägliche verzerrt und neu zusammengesetzt wird – eine Meditation über die sich verschiebenden, oft schwer fassbaren Grenzen zwischen Realität und retinaler Wahrnehmung, changierend zwischen Abstraktion und Figuration.

Mit seinem vielfältigen und umfangreichen Repertoire, das von Gemälden über Fotografien bis hin zu Spiegeln reicht, bringt Timoney die Flüchtigkeit der Zeit und die Unbeständigkeit der Bedeutung zum Ausdruck. Und auch wenn Beckett diesmal nicht explizit erwähnt wird, gehört er zweifellos zur Referenz-Crew. Seine Poetik – eine Ästhetik der Fragmente, nicht der Formlosigkeit, sondern der Formauflösung, eine Entropie der Worte – durchzieht Timoneys Werk, wovon schon der Titel Wrassem (2024), arabisch für „Maler“, chemische Behandlung oder Funkenbildung bei der Herstellung von Hasenleim, zeugt. Vielleicht ist Samuel Beckett der Papagei auf den Schultern des Seemanns, der mahnt: „Erwarte nicht, einen Sinn zu erkennen, erwarte nicht, das Referenzbild zu kennen“. Laut Timoney ist die beste Textinterpretation von Luckys Monolog in Warten auf Godot zweifellos keine Interpretation.

Die bemerkenswertesten Merkmale, die in den Rezensionen von Timoneys Werk immer wieder auftauchen, während die unerbittliche Brandung des Atlantiks an die irischen Klippen schlägt, sind die „Vielseitigkeit“ und „Heterogenität“ seiner „quecksilbrigen“ Praxis (Musik in meinen Ohren), die verschiedene Stile und Malweisen umfasst und sogar (ich habe das zweimal gelesen) die Illusion erweckt, man sehe eine Gruppenausstellung und keine Einzelausstellung.

Wie eine weitere literarische Inselgenossin Timoneys sagen würde: „Ich bin nicht einfach einer, ich bin komplex und viele“. Vielleicht ist er, bei allem Respekt für Virginia Woolf, einfach einer und komplex, und darin liegt keine kognitive Dissonanz. Nichts steht im Wege, die Dinge fügen sich zusammen. Er verspricht zu wenig und übertrifft die Erwartungen, während Künstler*innen, die glauben mögen, einen Stil, einen Namen oder einen Ruf verteidigen zu müssen, oft zu viel versprechen und zu wenig liefern.

Als Timoney mich bat, einen Text über diese Werkgruppe zu schreiben, sah ich darin zunächst eine Gelegenheit, seine Herangehensweise offen zu legen und sie zu entmystifizieren – die Betrachter*innen anzuleiten und sie aktiv an der Entschlüsselung von Sinn und Zweck der Arbeiten teilhaben zu lassen. Aber würde das nicht implizieren, dass die Werke nicht für sich selbst sprechen? Als jemand, der an die Spannung zwischen verbaler und visueller Bedeutung glaubt, neige ich trivialerweise zu der Annahme, dass dies nicht der Fall ist, und meine Praxis ist vielleicht der Versuch (πειρα), Bild und Bedeutung in Einklang zu bringen. Aber wenn die Einladung mit einem kurzen „Sei frei“ von einem Künstler verbunden ist, der Spiegelarbeiten macht, dann gibt es wohl niemanden, der diesen Aufruf zur totalen Freiheit und Selbsterkundung mehr zu schätzen weiß als ich.

Wenn ich an mein Spiegelbild in den blau-goldenen Oberflächen seiner Arbeiten Blue Mirror 1 (2022) und AuAgNY Mirror (2023) in seinem Berliner Atelier zurückdenke, kann ich mich des Eindrucks nicht erwehren, dass ein Text, der das Werk eines Künstlers kritisch reflektieren soll, mehr über den Autor aussagt als über das Werk selbst. Hier werden Autor und Betrachter blau und vergoldet. Ich muss an die berühmte Auseinandersetzung zwischen der intellektuellen Koryphäe Susan Sontag, der viele vorwarfen, ihre verkopfte Art, über Kunst zu schreiben, sei langweilig, und dem legendären und schwer fassbaren Künstler Paul Thek denken, der ihr schließlich, als ihm die Geduld ausging, entgegnete: „Susan, hör auf, hör auf. Ich bin gegen Interpretation. Man betrachtet Kunst nicht, wenn man sie interpretiert. So sollte man Kunst nicht betrachten.“ Wie die Geschichte ausging, ist bekannt. Sonntag widmete Thek ihre 1966 erschienene Sammlung kritischer Essays, und zwar aus gutem Grund: Der Band trug den Titel Against Interpretation.

Betrachte also die Kunst und sei frei!

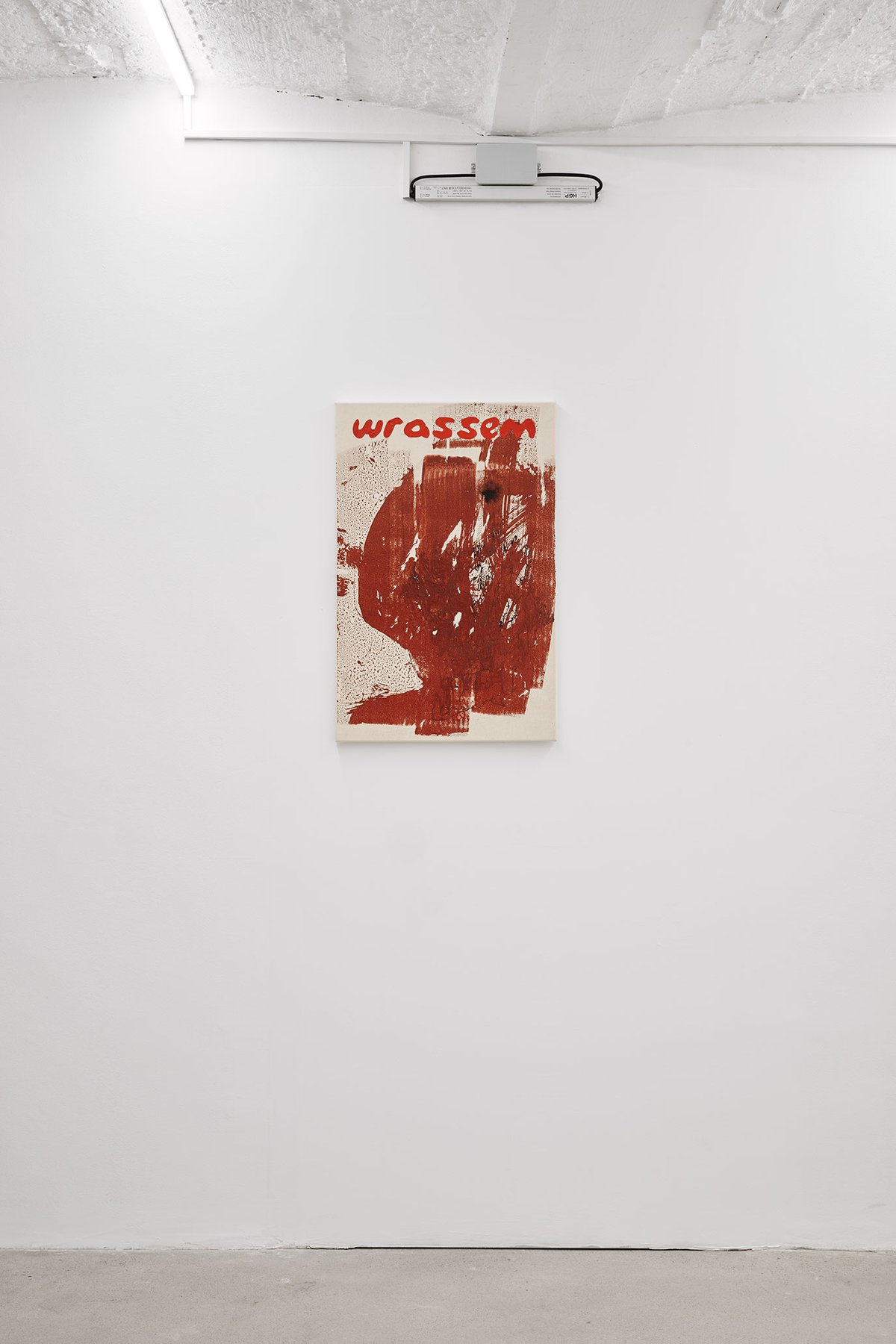

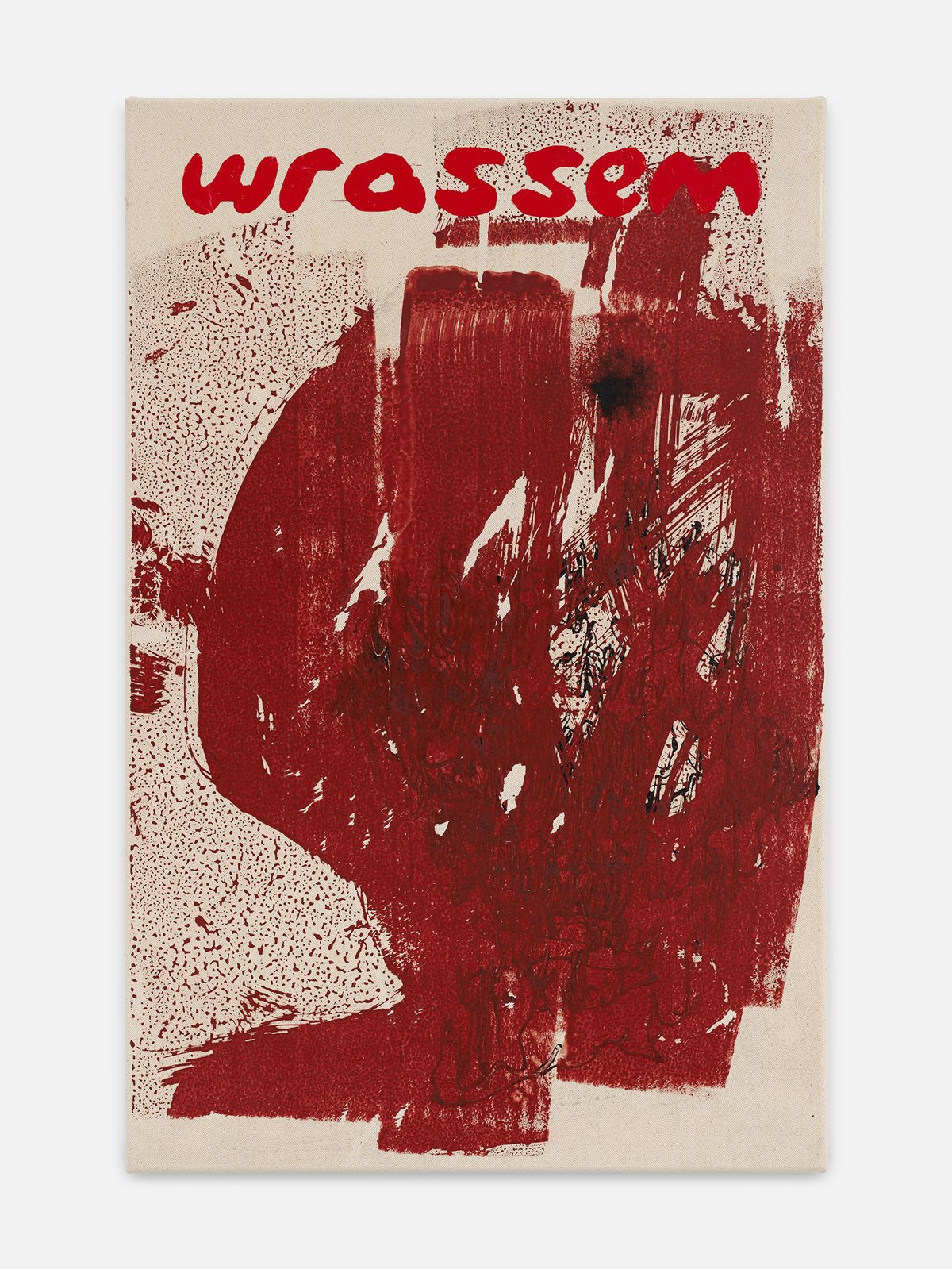

Wrassem

acrylic, ink and glue size on canvas

67 × 45 cm

2024

AuAgNYMirror

hand gilded glass

100 × 70 cm

2023

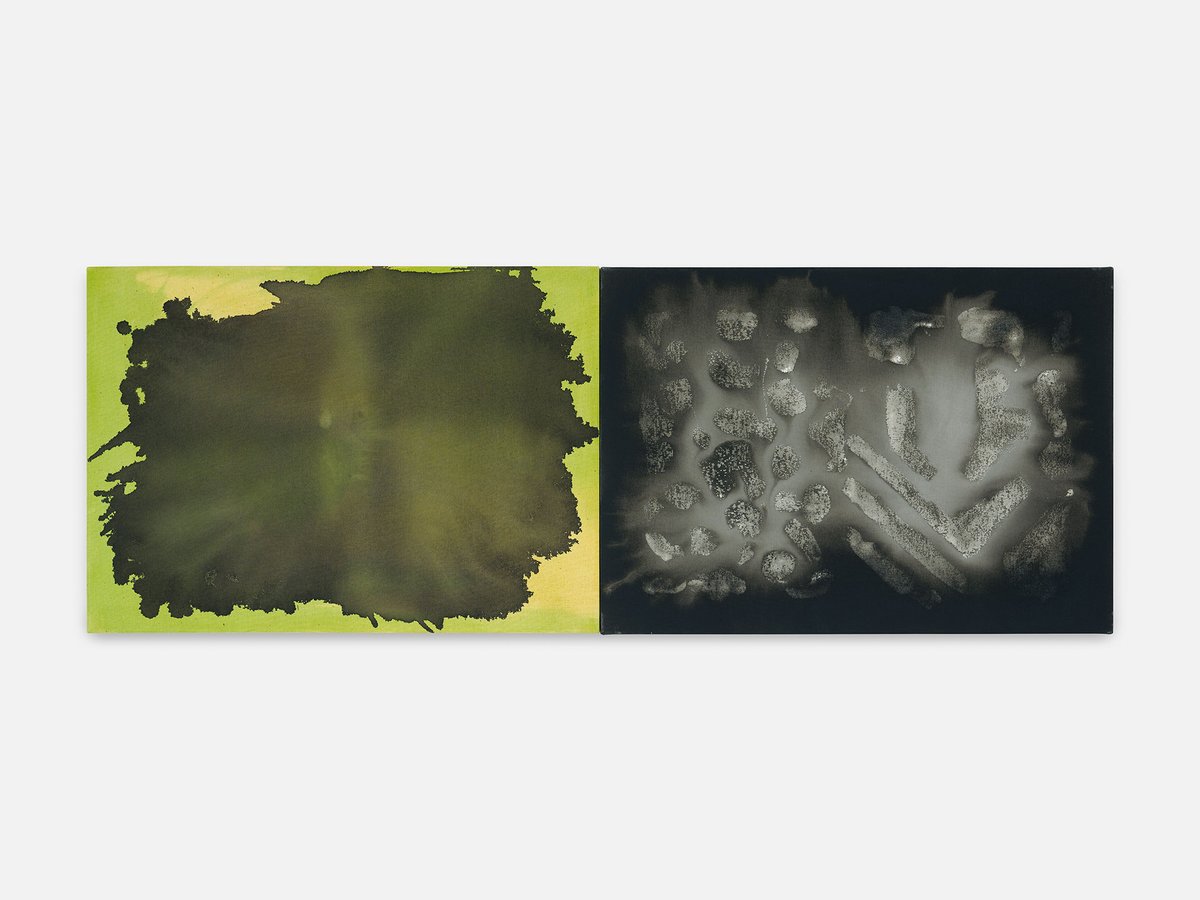

Dopo Franco Battiato

acrylic, ink and glue size on canvas

two parts, each 60 × 84 cm

2021

Mirror Waste Broken Mirror

treated mirror-making waste and glue size on canvas

70 × 100 cm

2024

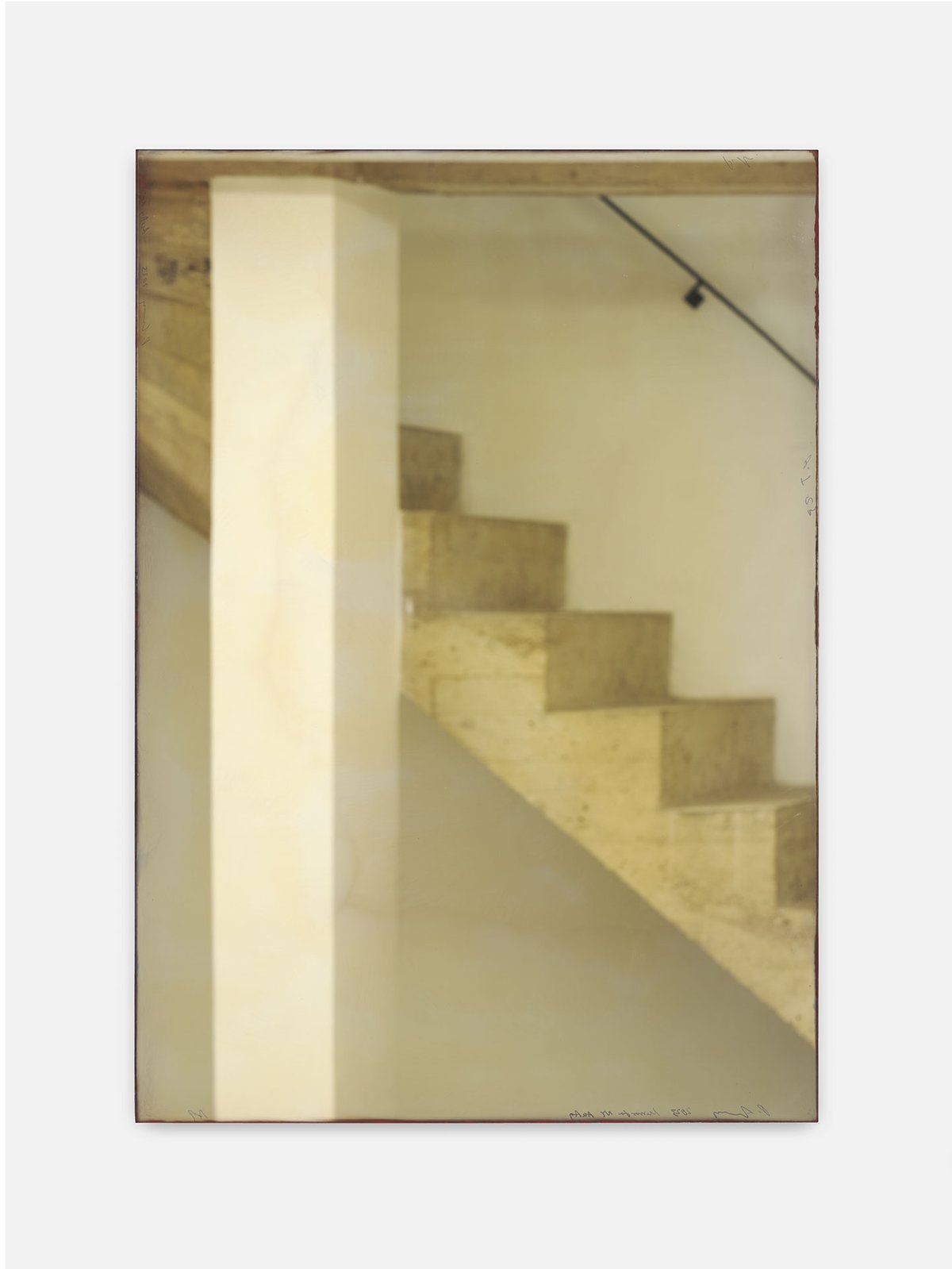

Membranes, Thins, Past

oil, acrylic and photo developer on canvas

182 × 218 cm

2022

Blue Mirror 1

hand silvered and leaded blue glass

84 × 60 cm

2022

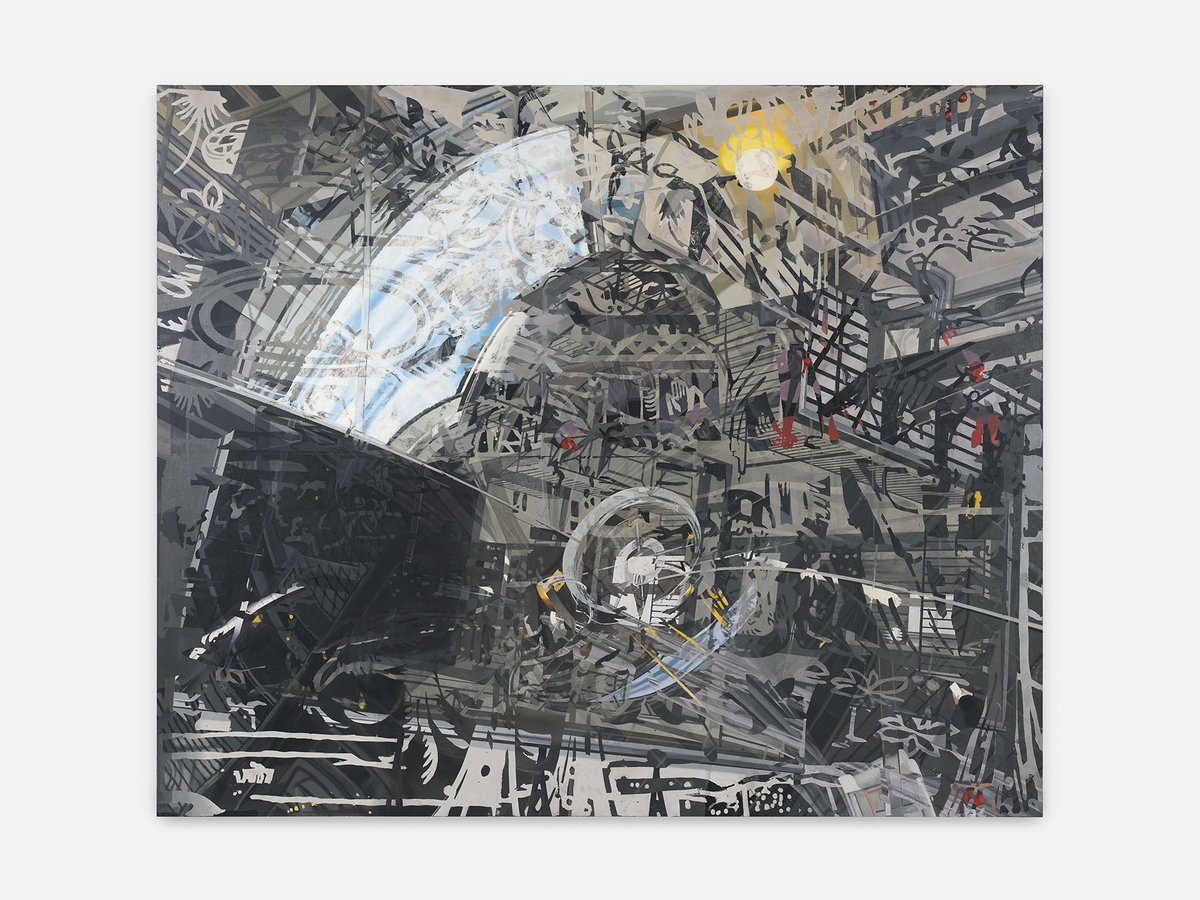

1.

Membranes, Thins, Past

Oil, acrylic and photo developer on canvas

182 x 218 cm

2022

2.

Mirror Waste Broken Mirror

Treated mirror-making waste and

glue size on canvas

70 x 100 cm

2024

3.

Blue Mirror 1

Hand silvered and leaded blue glass

84 x 60 cm

2022

4.

Dopo Franco Battiato

Acrylic, ink and glue size on canvas

two parts, each 60 x 84 cm

2021

5.

AuAgNYMirror

Hand gilded glass

100 x 70 cm

2023

6.

Wrassem

Acrylic, ink and glue size on canvas

67 x 45 cm

2024